Releasing Laughter

The art of writing laugh lines

By William S. E. Coleman

Professor emeritus, Drake University

Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.

Edmund Kean

That's a great tragedian speaking on his deathbed. Writing comedy is even harder than playing it. Tragedy is visceral. Find an inescapable conflict, and tragedy writes itself – well, almost. Comedy requires a risible situation, but to get laughs you must have a formidable arsenal of technique in hand if you hope to master that vicious, slavering beast we call an audience.

We must make that unruly entity lurking out there in the darkness laugh on our command, they must never get a toehold on us, or they will be in charge. If they gain the upper hand, we become beggars rather than commanders, and begging is the most pathetic kind of comedy. (See Red Skelton in his later years.)

The first building block for a comedy writer is the laugh line. From there, you progress to an exchange of dialog, to the scene, and then the act and the play itself. For the moment, I’ll concentrate on crafting the comic line.

Rhythm in the Comic Line

A comic line is not a one-liner or a joke. On occasion it may be quotable as a joke or a witty epigram, but it has to fit the character saying the line. The audience should never detect that author's presence in a line. If the character is not very bright, that must be reflected in the line. If the character is brilliant, that is a different problem. To do that you have to be as brilliant as your brilliant character. Scary? Yes. Remember, you have time to hone that brilliant line. People in real life – as your characters should resemble – don’t.

Let's examine a line written by Garson Kanin for his brilliant comedy, Born Yesterday. Paul Verrall, the writer who has been hired to educate Billie Dawn, Harry Brock's mistress, says, "I want everyone to be as smart as they can be. A world full of ignorant people is too dangerous to live in."

This is an apt observation, but it's not a laugh line. However, it is witty. What is wit? The dictionary says:

witty |ˈwitē| adjective ( -tier , -tiest ) showing or characterized by quick and inventive verbal humor : a witty remark | Marlowe was charming and witty.

It was a pleasure to sit and listen to their witty conversations

Humorous, amusing, droll, funny, comic, comical; jocular, facetious, waggish, tongue-in-cheek; sparkling, scintillating, entertaining; clever, quick-witted.

Kanin’s line requires intellectual recognition. A clever line like this can elicit a smile of realization and if the actor is brilliant, a light laughs. By the way, to have humor, you do not need to make the audience laugh out loud.

To understand how Kanin's observation moves, scan it. The first sentence is in strict iambics. That is, the initial syllable is unstressed, the second is stressed, and so forth. Iambs are the basis of Elizabethan blank verse. They are also at the root of the rhythms of most English language sentences. We speak at least three-fourths of our language with this scansion. Here and there he breaks the rhythm of his two sentences. This makes them more conversational.

However Kanin’s second sentence differs in rhythm.

A(soft) world (stress) (NOTE: CHANGE OF RHYTHM) full (soft) of (soft) ig (stress) nor (soft) ant (stress) peo (soft) ple (stress) is (soft) too (soft) dang (stress) er (soft) ous (soft) to live in."

Read this second sentence aloud. It does not move in a predictable manner. It shifts rhythms as it progresses. This second sentence ends with a soft syllable. A hard syllable would have pushed the line toward an outward laugh.

Breaking the iambic rhythm of a line lends surprise - and punch - to a line. Even so, most great comic lines are in iambics. That is, they are mainly in iambics. Note that word 'mainly.'

For example, Paul also says, "I've got nothing against a brain three weeks old and empty. But when it hangs around for thirty years without absorbing anything, I begin to think something's wrong with it."

The first three words of the first sentence do not scan as iambic, but the iambic beat moves in until the word 'wrong' interrupts the iambic beat. In doing so, it drives the line home cleanly. Dialog crispness releases a laugh.

The more elegant writer, Oscar Wilde, once said, "I can resist everything but temptation. Let's scan that: I (unstressed) can (stressed) re-sist ev-ry-thing but temp-ta-tion." Note we drop the 'e' in "everything' in ordinary conversation.

Stressing for the Actor

This is where the actor enters the scene. A clever actor, wanting to suspend the line before its pay-off will stress the usually unstressed 'but.' This causes a slight pause before the bomb is dropped and the laugh is released.

In addition to being beautifully rhythmic, this line uses repetition to hammer the laugh home. It is not iambic. By the way, I recommend that you study this great farce. It combines the brilliance of Oscar Wilde with a more modern sensibility – or should I say, insensibility?

The witty Dorothy Parker is credited with saying, "If all the girls at Vassar were laid end to end, I wouldn't be surprised."

While Parker wrote a few plays - mostly unsuccessful - this line could release a solid audience laugh if the actor just said it. A truly brilliant actor will give it no spin or punch. He or she would throw it off as a casual thought.

Winston Churchill said many epigrams that had a clever twist. Let's examine one of them: "Capitalism is the basis of the exploitation of man by man. Under socialism it is the opposite."

Technically, this is a paradox. It's also awkward in rhythm. Let me dare to edit the great man and cut a few words: "Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. Under socialism it's the opposite."

I think the wit of the line is released with this simplification. Why? Because the two sentences rhythm is improved.

Let's return to Oscar Wilde and a line from his The Importance of Being Earnest. He has the sophisticated Gwendolen Cardew say, "I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train."

The line fits the youthful pretensions of her character. Notice that the two sentences are in perfect iambics until "in the train."

At first this seems awkward, but it's a delaying action. Wit needs time to enter the audience's consciousness. There is a split second required for wit to create a synapse connection in our brain. The softening of that last prepositional phrase gives us that split second. Actors handle this with timing and holds. A clever writer builds in these very necessary hesitations. I advise all writers of comedy that they should make actors play on the writer’s home field.

The line is terse and cleverly devised. The word 'do' is softer than the end word “teach.” Shaw, with this slight shift of emphasis, drives his point home and releases a laugh, a laugh that rises out of a shock of recognition. You will also note that the final word ‘teach’ ends with a percussive consonant. Hard consonants release laughs if the line is well crafted. Softer vowel sounds do not.

A comedian friend of mine once said, “Turkeys aren’t funny. Chickens are.” By that he meant that the word “chicken” is more percussive than “turkey.” The difference is subtle, but the difference between a chuckle and a belly laugh can be determined by the subtle difference.

Subtle and Not-So-Subtle Exchanges

The next step in comedy writing is the development of repartee. First there is the feed line. Then there is the topper, or pay-off laugh line.

Let's examine this famous burlesque exchange:

STRAIGHT MAN: I've got a leak in my sink.

COMIC: Go right ahead. It's your sink.

The misunderstood 'leak' sets up the topper. I have seen this exchange set off a crisp, loud laugh that exploded like a bomb in the audience; but there usually was a split second pause before the laugh erupted.

In low comedy much can remain unspoken. Instead, the low comedian reacts with a take, or even a double take. An example can be found in the famous “Doctor Plumber” burlesque skit when a nurse in a doctor’s office during questioning a patient says:

TALKING WOMAN: I can see your predicament.

The low comedian responds with a take, and then looks at his fly. Nothing needs to be said.

Or this variation:

TALKING WOMAN: When the doctor is available he will ascertain your predicament.

Rimshot! Big take.

Now we move on to a higher plane. In Peter Barnes' magnificent The Ruling Class the insane Earl of Gurney believes he is God. When questioned he explains why he came to this conclusion:

CLAIRE: How do you know you're...God?

EARL OF GURNEY: Simple. When I pray to Him I find I'm talking to myself.

The Earl's literal approach interpretation of prayer contains an element of truth. What if he's right? What if we're God? The laugh that arises from this line is profoundly troubling.

While this exchange contains a disturbing element of truth, its ability to release a shocked laugh is rooted in the rhythm of the lean dialog. Again we encounter that word "rhythm."

I fondly remember a very big laugh that came early in Jean Kerr's witty, Mary, Mary. The playwright adeptly establishes the candid Mary's character when she has the actress (played by Barbara Bel Geddes in the original production) pick up a small candied object from a bowl on a table. She studies it with intense curiosity and asks, "What is this?"

Another character says, "It's a dried apricot."

Mary replies with a purred drawl, "Good, I thought it was a human ear."

We immediately know this is no ordinary ingénue. We also laugh with this touch of black humor. More importantly, a character is revealed immediately after she enters for the first time. This line is a gag, but it arises out of character. It is not there just for a laugh.

The Masterful Oscar Wilde

Now, let's move on to a longer exchange, this one in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

ALGERNON [to GWENDOLEN] Dear me, you are smart!

GWENDOLEN: I am always smart! Am I not, Mr. Worthing?

JACK: You're quite perfect, Miss Fairfax.

GWENDOLEN: Oh! I hope I am not that. It would leave no room for developments, and I intend to develop in many directions.

This wonderful exchange has rhythm and wit. It builds nicely to a climax as it moves from a smile to a big laugh.

Speaking of developing in many directions, Wilde has an exchange that deals with this:

ALGERNON: All women become like their mothers. That is their tragedy. No man does. That's his.

JACK: Is that clever?

ALGERNON: It is perfectly phrased! And quite as true as any observation in civilised life should be.

JACK: I am sick to death of cleverness. Everybody is clever nowadays. You can't go anywhere without meeting clever people. The thing has become an absolute public nuisance. I wish to goodness we had a few fools left.

ALGERNON: We have.

Those two words, "perfectly phrased," are our challenge as writers. Remember, a line can be "perfectly phrased" whether it comes from a London aesthete or a beer swilling mill worker.

It at this point comic playwriting begins. Each succeeding exchange should build and provoke even more laughter, but each exchange must move along the plot of the play. Each must be organic to the play. How do you do this? You let your characters react to each other, and you have to live the scene with them as you write.

As this happens, a clever writer shifts from one kind of laughter to another. The biggest laugh should not come first. Above all a skilled playwright knows when to top a sequence, back off, and build another sequence. Too much consecutive laughter wears out an audience.

While the writer, usually after a spontaneous draft, constructs these comedic building blocks, he or she must also tell a story. To do all this is relentlessly demanding. If a laugh line doesn’t contribute to the advancement of the story, cut it. If the laugh line is out of the stylistic tone of your play, throw the line away. If it is a good line, store it in a notebook for future use.

Finally, in all comedy there is stylistic coherence. One cannot shift from the formalized writing of an Oscar Wilde to the natural and modern dialog of Garson Kanin, and certainly a shift from Wildean dialog to burlesque low comedy would be too much of a shock to any audience’s system. Generally, the first laugh sets the stylistic tone of a scene. I call this “the signal.” Once that first laugh is released, the audience will think that is the tone of the comedy to come. In other words, you can’t have a character pick his nose, flick the snot away, and speak an elegant epigram. Come to think of that, doing that might be very funny.

Objectivity in Comedy

There are many kinds of laughter. These include belly laughs, gut busters, giggles, sniggers, groaners, guffaws, laughs until you cry, fall down funny laughs, roll in the aisle laughs, nudge-nudge-wink-wink laughs, and pee your pants laughs – to name a few. Attaining a coherent style requires taste – or a lack thereof – and discipline.

Does that sound complicated? Of course, it does. That, dear reader is why the dying Edmund Kean gasped, “Comedy is hard.”

Yes, try writing comedy in your own home; but do it at your own risk. And if you can get your comedy before an audience, the risk is even greater. What if they don't laugh? That is the ultimate nightmare.

One final piece of advice: If your brilliant play fails to evoke laughter, blame it on the director and the actors.

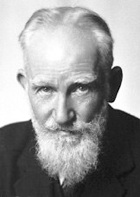

George Bernard Shaw